Optimum potential, what is it? When we have a child, we begin the journey by first meeting their survival needs. When that rhythm is established, we begin to look towards the future. What do we need to do to give this child the greatest chance to reach their optimum potential?

Let’s begin by defining the term “optimum potential” in this context.

In the first two years of life your child’s nervous system is developing faster than in any other time in their lives. This is the time when they are laying the foundation for the innate potential that they will depend on for the rest of their lives. From age 2-6 they are integrating their nervous system and fine tuning it into a functional system that will determine how they interact and adapt to the world around them, into and through adulthood.

As parents and caregivers, we strive to introduce those things to them that best support their healthy development. Proper rest, good food, a safe and stimulating environment, physical and emotional support, offering direction and establishing foundational boundaries, and supporting them in creating a healthy internal and external ecosystem.

The ability to adapt to life’s challenges is mitigated by many factors, including genetic predisposition, quality and quantity of meeting basic needs, opportunity to expand neurological development, and a healthy functioning nervous system. Dis-ease, dysregulation, neurological diversity, adaptation, are all predicated on the child’s nervous system’s ability to adapt to their environment and the challenges they face.

We often try to put labels on a child’s struggle to adapt or self-regulate, to allow us to describe the activity or behavior. Things like ADHD, ASD, DCD, ODD, OCD, DMDD, etc. are often used as descriptive patterns of behavior or challenges. We must remember these are not the child’s identity but a “symptom” of their inability to react to or navigate effectively the challenges in their world.

What we often choose to do as parents or caregivers in these situations, is attempt to mitigate the external behavior patterns to fit into what would be considered a more “normal” reaction or response. We may employ external controls including, behavior modification, repatterning exercises, regulating the environment, nutritional modifications or supplementation, and other tools to help support the child.

Another approach is to support the internal adaptative mechanism – the central nervous system – by increasing its processing and adaptative threshold. This will create a larger internal bandwidth to allow the child to better cope and respond to stressors (demands or events, physical, emotional, environmental, or social, that place load on a person’s system). Establishing a stronger, more adaptive, better functioning mechanism by which the child can navigate through life – their nervous system – is an impactful way to allow them to reach their individual optimal potential.

What if we thought of disease in another way?

Let’s look at our current paradigm. Disease is something to be fought, it is caused by and external source that “attacks, invades, assaults, overcomes” our immune system. It is defined as “an abnormal condition that affects the structure or function of part (or all) of the body, generally associated with specific signs and symptoms. “It is how the body’s internal balance is disrupted, how that disruption produces observable effects, and how ‘medicine’ intervenes to restore function or slow progression.”

Now let’s look at another model. Right now, your body is maintaining thousands of delicate balances – pH, blood sugar, mineral ratios, temperature – through internal, autonomic (automatic) feedback loops. This is called a state of homeostasis. The fact is that we don’t only live in the external world but in our own internal changing and adapting environment.

When this internal environment stays balanced, you have energy, balance, clarity, resistance to disease, i.e. a state of health. When stresses, physical, mental, emotional assault this balance continually, your systems begin to fail if the internal mechanisms are not supported sufficiently. Your nervous system becomes overloaded, constantly having to adapt and maintain a fight or flight mode (the antithesis of a healing internal environment), your immune system exhausts itself, having to constantly defend against both internal and external stressors. The symptoms you develop – the arthritis, diabetes, chronic fatigue, cancer – aren’t random attacks by germs. They’re the predictable result of your internal environment breaking down.

This is where the problem lies. If we are convinced that disease comes from the outside, then our personal responsibility for our own health becomes secondary, and we begin to depend on outside sources or experts to save us. This compartmentalized disease-centered or “reductionistic” model disarms us, weakens our trust in our body’s capacity to maintain and health and heal. The United States spends over a trillion dollars a year on this “healthcare” model, about 17.6% of its GDP. To give you’re a concrete idea of the costs, we spend about $14,570 per person, per year, while other high-income countries average around $7393 on their healthcare system. Despite this additional spending the U.S. has some of the worst health outcomes compared to many other developed nations, including lower life expectancy. We are 33rd out of 38 OECD countries, making us near the bottom among high-income countries. We also have some of the highest cancer rates, chronic disease rates (HHS stated that 54% of the children in the U.S. have chronic diseases), and levels of pharmaceutical consumption. This is not a sustainable process.

On the other hand if we thought about taking back responsibility for our own health, including the daily choices we make, the environments we choose to be part of, how we react to stresses (these will not go away) we could shift this mentality and the create some true “healthcare” paradigms instead of a sickness care model.

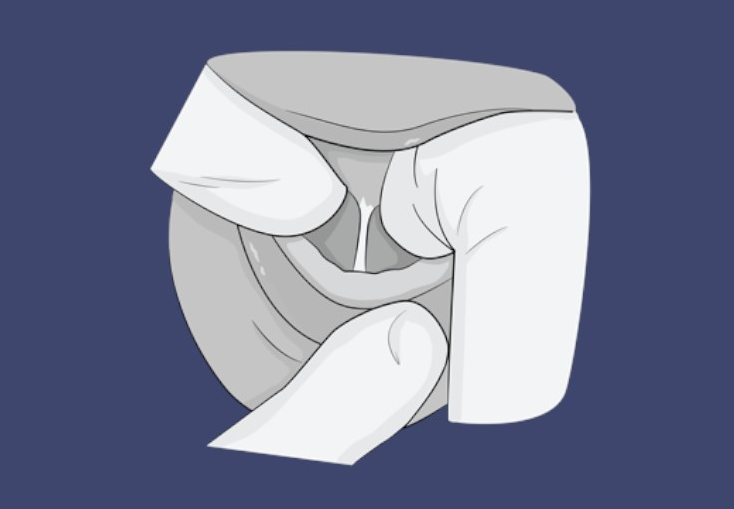

Salutogenisis, a term developed in the 1970’s, by sociologist Aaron Antonovsky (the concept is the basis for the chiropractic philosophy which D.D Palmer originated in 1895), focuses on the origins of health rather than the cause of disease. The question it begs is “What keeps this person well?” instead of the current model of “What made this person sick?”. What the salutogenic model chooses to do is to find ways to support the body’s innate intelligence (that internal mechanism/energy/force that is responsible for maintaining health from within). The goal of the chiropractic adjustment is to remove interference to and enhance the ability and adaptability of the nervous system to allow the innate healing ability of the body to express itself to its full potential.

So, while many people seek chiropractic care for a subset of symptoms, based on what we now see is at best an antiquated model, the true purpose of the chiropractic adjustment is to help create a more adaptive, responsive, and functional nervous system to allow the body to do what it does best, maintain a balanced nervous system (the controlling system of all other systems in the body) and create health and healing from within.

Featured Articles

View our articles on chiropractic technique, practice management, research and philosophy.