Swaddling has been a common practice across cultures for centuries. Parents are often told it helps babies sleep better, keeps them calm, and prevents startle reflexes from waking them. While short-term soothing may be a benefit, the long-term neurological and structural consequences of swaddling — especially once an infant begins to roll — demand a closer look.

As chiropractors who work daily with the developing nervous system, it’s our responsibility to help parents understand what swaddling does beyond sleep. When you bind an infant’s body tightly, you limit not only their movement but also the sensory and neurological input that movement provides.

The Neurological Input Infants Need

From the moment they are born, babies depend on movement to wire their nervous system. Primitive reflexes — rooting, Moro, tonic neck reflex, and others — all depend on free limb and trunk motion for activation and integration. Every kick, arm wave, or stretch contributes to proprioceptive and vestibular input that shapes the child’s motor patterns and neurological organization.

When infants are swaddled, their ability to explore these movements is restricted. Over time, this reduces the input necessary for proper integration of primitive reflexes. Reflexes that fail to integrate can delay milestones such as rolling, crawling, and eventually walking. These delays ripple outward, affecting balance, coordination, and even emotional regulation later in life.

I emphasize the role of free movement in fostering neurological certainty. The nervous system develops through repetition and feedback. Swaddling may quiet a baby, but it deprives their nervous system of essential “practice” in moving against gravity, organizing motor pathways, and building the foundation for higher brain function.

Cranial Molding and Structural Concerns

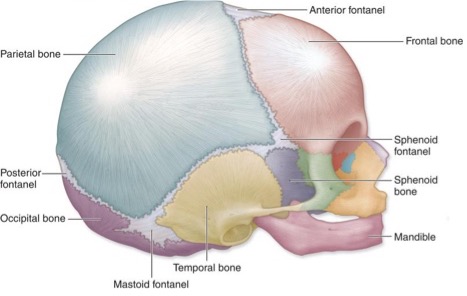

Beyond neurological input, swaddling also has implications for cranial development. The bones of an infant’s skull are still soft and malleable, designed to adapt and grow in response to natural movement and the pull of muscular activity. When an infant is swaddled tightly, their ability to reposition is compromised. This not only increases the risk of positional plagiocephaly (flat spots on the skull) but also interferes with the dynamic motion of the cranial bones and sutures.

Cranial molding issues don’t just affect head shape. They can alter the mechanics of the cranial base, influencing jaw development, airway capacity, and even neurological signaling through dural tension. What seems like a benign bedtime practice can set the stage for challenges that present much later in childhood — difficulty with breathing, speech, or posture — all rooted in those early restrictions.

The Turning Point: Rolling Over

If swaddling is used at all, it should stop when a baby shows signs of rolling. At that stage, swaddling becomes not only developmentally restrictive but also physically dangerous, as it raises the risk of suffocation. Babies need to roll, push up, and use their limbs freely to develop strength, coordination, and spatial awareness.

When parents ask, “When should I stop swaddling?” the safest and most developmentally supportive answer is: sooner rather than later. Freeing the infant’s body for natural movement supports both their neurological wiring and their structural growth.

Some Better Options

Here are some alternatives that foster both soothing and development:

- Encourage skin-to-skin contact, which regulates infant physiology without restricting movement.

- Promote supervised tummy time from the earliest weeks, building core strength and cranial motion.

- Vary head and body positions during sleep and awake time to prevent positional issues.

- While babies may startle or fuss more when not swaddled, those movements are critical to their growth.

Conclusion

Swaddling may promise a quieter night, but the cost is often hidden in a child’s delayed neurological development and altered cranial growth. Movement is the language of the developing nervous system. When we restrict that movement, we restrict the input that builds the foundation for a child’s lifelong function.

Featured Articles

View our articles on chiropractic technique, practice management, research and philosophy.